Wednesday, May 14, 2025: Historical Tidbits

An historical fiction author's dilemma!

Welcome, I’m Mary Louisa Locke, the author of the USA Today best-selling Victorian San Francisco Mystery series and the Caelestis Science Fiction series. In this daily newsletter, I reflect on my life as an indie author trying to age gracefully. Occasionally, I will also publish some of my shorter fiction in this newsletter to read for free.

Daily Diary, Day 1715:

Brief check-in: Walks going well, another long phone call with daughter yesterday, plus scheduled phone call in afternoon. But haven’t been writing…mostly because lack of time, but also to let bursitis calm done. The effect has been swelling is not just down, but the elbow looks almost back to normal. Will give it another day, then see if starting back up writing causes it to swell again. If so, won’t stop me from writing, but I might so more breaks.

Meanwhile, as promised, the following will be essentially a rewriting of a piece I did for my blog in 2013, as I was doing the research for Bloody Lessons, the third book in my Victorian San Francisco mystery series.

Dong the research, I had run across the following quote from an article.

“Last evening, as I was hurriedly walking along Dupont street, near Post, in the gloaming, I saw before me a young dude, who, instead of minding his business of walking decently, was projecting his face and hat into the visage of his girl companion to the left, while with his dexter paw he twirled a light cane, which extended half way across the curbstone, and which I tried to escape, but which, notwithstanding, hit me square upon my nose, which is a long one.” —San Francisco News Letter and California Advertiser (January 9, 1886).

When I read this quote, I laughed out loud. You see, I am a fan of the movie the Big Lebowski, whose main character called himself “The Dude” and spoke of himself in the third person, and, as a result, the use of the word dude in this 19th century context cracked me up.

The next thing that occurred to me is that if I tried to use the word dude in my 19th century fiction, I would probably bring the reader right out of the moment because it would sound so modern. As I investigated the word and its meanings, I discovered that the term has undergone a profound transformation from its 19th century origins to its modern-day uses.

In 1886, when the above paragraph was written, the term dude was relatively new. A history of the word in says that the term first appeared in print in the 1870s in Putnam’s Magazine, making fun of how a woman dressed. However, a variety of sources I found agree that by the 1880s “dude” had become American slang for a man who was extremely interested in dressing and acting in the latest fashion, often copying the style of the English upper classes (and often referred to as a Dandy.

Clearly based on this newspaper article, by 1886 article, people in San Francisco would be familiar with the term, since the author felt comfortable using the term when complaining about modern mores as he described the rude young man who was strolling down a San Francisco street, twirling his cane.

At this exact same time, the word was taking on another, albeit related, meaning, as the term dude began to be used (for the first time in 1883 in the Home and Farm Manual) to describe men from the city (Easterners) who demonstrated their lack of knowledge about rural life (the West) by behaving and dressing inappropriately.

These two uses of the term were clearly related, since to a working rancher or farmer there would be nothing more ridiculous than some dude (whether from an Eastern or a European city), who came to the American West, dressed in fancy duds and pretending to be a cowboy.

By the early 20th century, the term began to be applied to ranches that catered to these eastern “city slickers.” In fact, in the mid 1960s, my very suburban family spent a week on a “Dude Ranch” in upstate New York, where we rode horses, went on hay-rides and did square dances in a barn. If you had asked me the meaning of the word then, I would have clearly understood it to mean “city slicker.”

Yet, by the late sixties the term had also become a general form of slang used by men when addressing other men, and it seemed to have emerged within urban Black culture. Unlike its original meanings, this was a positive form of address, and it had nothing to do with city slickers.

Pretty quickly, whites who wanted to sound cool, expropriated the term (it shows up in the movie, Easy Rider) and by the mid-to-late 1970s, just about the time I arrived in Southern California, the term became associated with that region, specifically attributed to “stoners, surfers, and skateboarders.”

In 1982, Sean Penn’s character, Jeff Spicoli, in the movie Fast Times at Ridgemont High, personified the kind of young man who was called, and called others, dude.

While this new use of dude, as an informal form of address among young people, began to predominate, the older meanings didn’t fade away completely. My young daughter, for example, loved the TV show Hey Dude (1989-1991) that was about a dude ranch, not stoner skateboarders.

Nevertheless, in my own mind, this earlier meaning of the word was wiped out completely after I watched Jeff Bridges in the Big Lebowski in 1998.

This movie about a grown-up man, Jeff Lebowski, whose days are filled with bowling, smoking weed, and sliding through life, has become a cult favorite, and it has created an indelible image of what could happen to the Spicolis of the world if they never grew up.

Interestingly, when I thought more about it, I realized that the writers of the movie (the Coen Brothers) were clearly aware of the changes the term had undergone from its earlier origins. For example, the movie is narrated by a character (called The Stranger and played by Sam Elliott), who is a quintessential cowboy. A cowboy who wryly references the change in the meaning of the word dude from city slicker to stoner slacker in his opening monologue in The Big Lebowski.

“Way out west there was this fella… fella I wanna tell ya about. Fella by the name of Jeff Lebowski. At least that was the handle his loving parents gave him, but he never had much use for it himself. Mr. Lebowski, he called himself “The Dude”. Now, “Dude” – that’s a name no one would self-apply where I come from. But then there was a lot about the Dude that didn’t make a whole lot of sense.”

What does this all mean for me as a writer of historical fiction set in the 1880s?

First of all, I can’t prove that any of my characters would use the word dude, in either of the earlier meanings–of dandy or city slicker–in 1880, when my next book was set, since I can’t prove they would have heard of it living in San Francisco before 1886. However, the fact that the writer of the 1886 quote used the word without feeling the need of any explanation does suggest that I would not be committing any major historical inaccuracy if I did have someone use the word in either of its original meanings (dandy or city-slicker.)

Yet, when I read the word in the 1886 article, all I could think of was Jeff Lebowski, in his ancient knitted cardigan, sloppy t-shirt, and baggy bermuda shorts, ambling down the street with his bowling bag in hand, and I was no longer in the 19th century. I was certainly not thinking about a young man who was “extremely fastidious in dress and manner.”

Here the modern meaning and use of the term was just too far from its origins to be an effective word to use in a work of historical fiction set in 1880. Consequently, it was with reluctance I gave up trying to figure out in what context one of my characters could call another Dude.

On the other hand, I did use the word hoodlum in my second novel in the series, Uneasy Spirits, even though, like dude, it was a form of slang that was very familiar to me growing up in the 1950s and early 60s. I made that decision because, first of all, I had proof that it was a term that would have been used in 1880, and secondly, because the meaning hadn’t changed all that much over time. A hoodlum in the 19th century and in the 1950s was a young man “who behaves in a rowdy or intimidating way.” Merriam-Webster dictionary.

This Wikipedia article places the first use of the word in 1866, in the San Francisco Chronicle.

And to demonstrate that my characters would know its meaning, I included a real newspaper quote as part of an early chapter heading in Uneasy Spirits.

“Shortly before 12 o’clock last Friday night officer Waite…was set upon…by a crowd of Barbary Coast hoodlums, who struck him several times over the head and face with a billet of wood.”

—San Francisco Chronicle, 1879

I then used the term numerous times in the book in ways that implied its meaning. None of this assured that the term might not pull a reader out of the story, but at least I knew I wasn’t being inaccurate, and I thought that readers might actually enjoy learning how old the term was.

So, just a glimpse into how both historical fiction and science fiction can cause problems for an author in deciding what words might or might add or substract to a story.

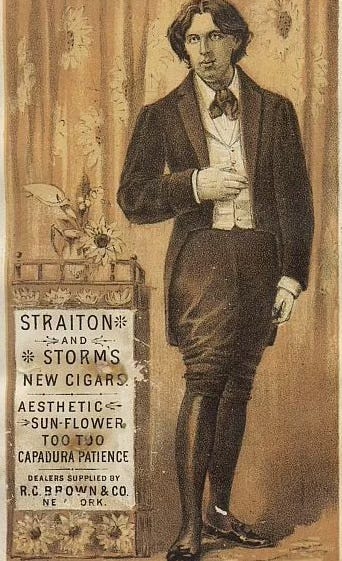

Oh, and this photo of Oscar Wilde, an Englishman who made a successful tour of the west during the period, shows what a man who considered himself a real dandy looked like at this time.

Everything I publish in this newsletter is available to anyone who subscribes, but I am always pleased when someone shows their appreciation for what I am writing by clicking the button below to upgrade to paid, thereby providing me more resources so I can spend more time writing my fiction and less time marketing. In addition, please do click on the heart so I know you’ve been to visit and/or share with your friends, and I always welcome comments! Thanks!

Yeah, well, that's just like your opinion. 🙂 Also now I have the Bowie song in my head.

I remember having to explain to someone older in the early 90s that "dude" is a general term regardless of sex or gender. Because "dudette" sounds silly. It still had the "dandy" meaning even in L.A. when a (male) friend saw me dressed fancier than usual and said "Whoa, you're all duded up!"

I have to say since following you, writing professionally is nothing like I thought it was. Thank you for the education!